Learning To Lie

Children need two things to lie, Mum told me. The first is the ability to imagine what another person is thinking. The second is an understanding of rules and what happens when they are broken. Children understand at an early age that, if they confess, they may be punished. If they lie, they might not be.

That's why I told the biggest lie of my life, aged seven, to a policeman in Rippingale.

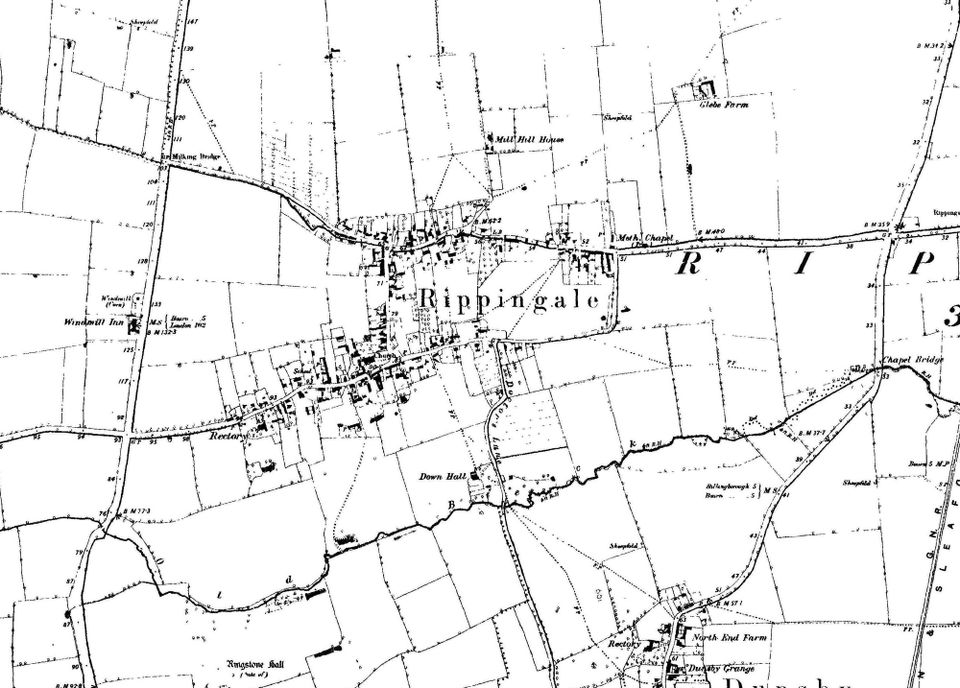

Rippingale. Even the name sounds made up. One to add to the list of implausible British village names: Boggy Bottom, Giggleswick. Little Snoring, Old Sodbury, Shitterton. But the village was no fabrication.

I lived there as a child, from the ages of three to ten, in that abandoned place out in the fens. Rippingale was a dwelling forged from the mud, surrounded by dykes and the flatlands of Lincolnshire, yellow fields forever, a clutch of jackdaws, that dark pine copse full of red deer.

We moved there because Dad got a salaried position selling aluminium windows, better than that commission work he was doing in Portsmouth. Cousins lived nearby, too. Mum found work, she always did, with her degree in zoology and statistics. And the village school took me in, a year early, because it would close without more pupils. I don’t think that’s why my parents had six children though.

How many people lived in the village? 600. Less, perhaps. Was our family one percent of the population? It felt like it. Our phone number had four digits. Mum loved that house with its solid fuel heating and its proper garden and everyone was so nice to her when we arrived. Grandma and Grandad came to stay and she beamed.

The bus came once a week on market day. The fish and chips van arrived from town on a Thursday. Once every few months, the travelling library came and sometimes Mum bought me new stories.

I remember autumn most clearly, when the farmers would set fire to the fields, clearing the stubble, and flames raged and smoke filled the house. The world grew cold quickly after the fields burned out and the evenings got dark. Mum drove more slowly in winter, crawling alongside the ditches full of floodwater, past the old cemetery and the weeping ash in the churchyard. In 1987, after the hurricane, it snowed so hard that the local doctor drove to the surgery on a tractor. Us kids knew all the makes: John Deere, Massey Ferguson, and the trusty blue Fords. The dead tractors rested in farm boneyards that Mum forbade us to enter.

Daisy was one year old when we moved. I never had anything against her. She was a good kid, no bother, quiet.

Speak up, Dad would tell her.

And then Zoe came and I accepted her too. When Dad told me that they were having another baby (Billy, their fourth child), I burst into tears though.

Why are you crying? Dad asked.

I couldn’t tell him. What could I say? They took up a lot of space, these brothers and sisters. And Mum's attention was divided, like a piece of paper that can only be folded so many times. I understand now, it was a lot.

When I began to lie, to get Daisy in trouble, it was nothing personal. Mum sent us upstairs to wash our hands before teatime and I bit myself on the arm. It didn’t hurt, but it left a convincing mark.

Mum! I screamed.

What now?

Daisy bit me!

I proudly demonstrated the flesh, pink with two rows of white teethmarks, indents in my skinny forearm.

Go to your room, Daisy.

Mum and I have different ideas about when this incident took place. She thinks it was later, that I was older. But I remember practising faces in that bathroom mirror, fake crying, trying to look sad and shocked at the same time. It was a sort of experiment. I wondered what exactly would happen if I made something up. How far could I take it?

Children have to learn how to lie, Mum said, much later.

That’s how I tricked her. I learned to match my facial expressions with the tone of my voice and the words that I spoke. I was excellent at lying, better than she realised.

Sometimes lying was okay, like when I used to go and stay with Grandma. Grandad was tall and impressive, he was the one that got me supporting Arsenal. He liked lawn bowls and was good at it and the house was full of trophies. The garden wasn’t very big and Grandma walked very slowly and I didn’t like the food much. But I said I did and then Grandma and Grandad didn’t get upset and Mum said that was okay.

Rural village life afforded us children the freedom to roam. It was the eighties. During the summer holidays, even as very young children, Mum was happy to let us leave the house unattended in the morning. We only came back when it got dark or we were hungry.

Matthew was my best friend in the village. He fulfilled all the criteria: sported a shellsuit, read Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comics, owned a Lego Millennium Falcon. I had none of those things but we bonded nonetheless and formed the village skateboard club.

One day, wandering the village and looking to expand our membership, we met Shawn. He was a bigger kid with expensive trainers and a tough haircut. Shawn didn’t have a skateboard, but he did want to show us something. He took us to the old pinfold in the centre of the village.

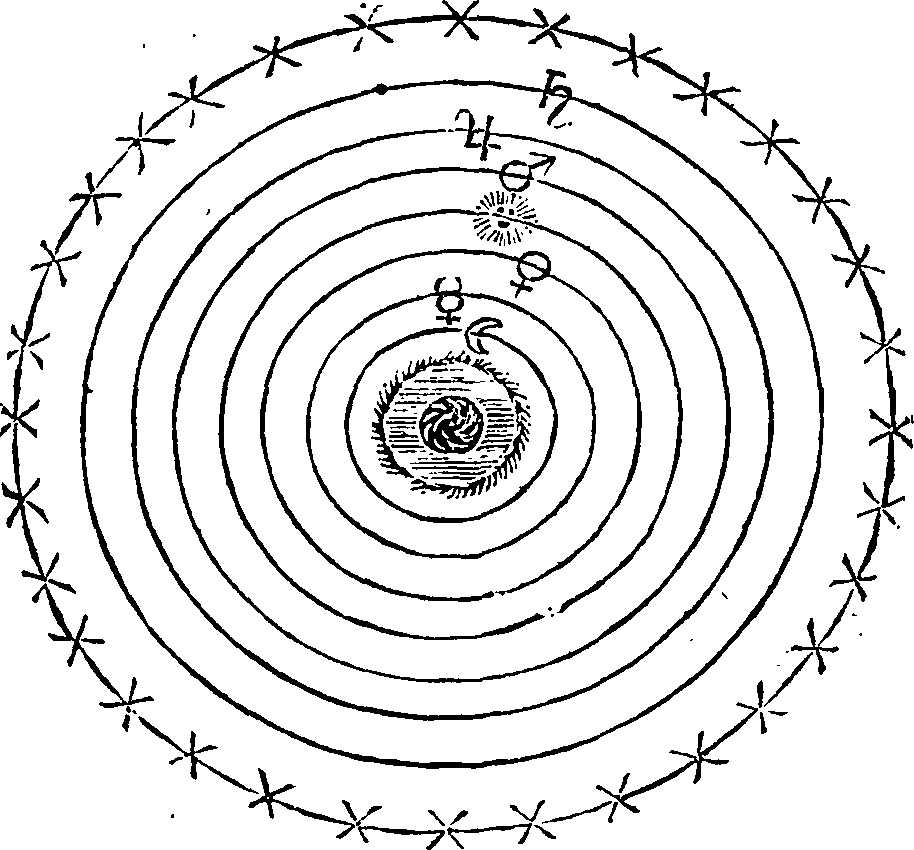

A pinfold is where they used to keep animals when they got lost, Mum told me. It was a small, enclosed area, boundaried by dry stone walls, laid without mortar. This one dated back to the 12th century.

I'm not sure why I vandalised it. But I did. We were playing house, I think, and the house had no window so I decided to unpick the stone wall in order to make one. I didn’t know that I was dismantling hundreds of years of history. All I knew was that I had made a fine window, through which I could see the house opposite. The house opposite, it turns out, could see me too.

The policeman knocked at my parents’ door sometime that evening. My parents invited him into the living room and called me down from my room.

The policeman asked what I had been doing today.

Playing in the village, I said.

He asked me if I had damaged the wall.

I denied it. It wasn’t me, I lied.

The policeman asked again.

What wall? Don’t know any wall.

Other people had seen me do it, witnesses, the policeman said. Shawn told me you were there.

He's out of the skateboard club, I thought.

Dad chimed in. Listen to me, son. Lying will only make it worse.

Whose side was he on?

You have to tell the policeman if you did it, Mum said, using her kind voice, not her cross voice.

I dug in. It wasn’t me.

We’re not getting anywhere, said the policeman.

You might not be, I thought, but I am.

Dad let the policeman out, apologising, we’ll have a word with him.

When Dad came back in, Mum looked at me and I broke immediately.

I was wailing and inconsolable, she always says, floods of tears, confessing over and over, talking about how I didn’t want to go to prison. Mum says she was shocked, felt betrayed somehow. Her first-born had always done what he had been told, but that day she felt that she lost control, she was no longer in charge.

As a punishment, she grounded me for a month. No more village adventures or skateboard club. The Millennium Falcon was off-limits. I had to help a dry stone waller repair the damage too. It wasn’t much of a punishment, really. In fact, I secretly enjoyed it, layering the flat stones and learning about old things.

Lying is a sign of intelligence, Mum told me. Clever boy, going to school a year early. Just trying things out. She said that lying and caring are not so far apart. Children have to learn what others are thinking and how they are feeling.

Dad did not think the punishment was enough. Soon after, he joined the police force himself, recruited by the policeman that came to see me.

When my Grandad died not long after, I found Mum sobbing in the living room. It didn’t make sense, because she seemed so happy earlier that evening. She and I had been watching out for barn owls when we saw a fat hedgehog and its baby roll out of the bushes towards the lights of the house and Mum held me up to the kitchen window to look.

I had never seen her cry before. I asked what was wrong. She said that she was just sad, that was all. People cry when they are sad. She said the wall and the arm biting was all forgotten, that there were more important things and that I was a good boy. I put my arms around her, because that is what she did to me when the policeman left and, even though it took me a long time to do so, I had told the truth and she said she was proud of me and that was the end of it.

So, with the stone walls newly repaired, and the fires in the fields not yet extinguished, I put my arms around her and I said it was okay, everything will be okay, and that this time I was telling the truth.

Thanks to my Foster editors, Jesse Germinario and Chris Angelis. And thanks to Julia for putting up with my loud typing during our recent self-isolation.

Like what you've read? Feel free to subscribe to my newsletter, or tell a friend and they too will get creative non-fiction and essays exploring different themes, every Saturday.

"The first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It has potential, but it’s not. Your killer taste is why your work disappoints you. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing. You gotta know it's normal. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions." – Ira Glass